Junk bond funds are seeing record outflows. This has been described as a ‘six-sigma event’, in other words, six standard deviations away from the mean weekly flow, something that if normally distributed should only be expected once in millions of years.

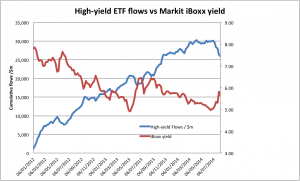

By definition that’s unusual, but in the context of broader investment in riskier corporate debt, how significant is it? Let’s start by looking at exchange-traded funds that invest in junk bonds. This is the most liquid segment of the market, and market leader Blackrock has spoken of using ETFs to replace traditional bond investing. Since 2011, $26 billion has flooded into high-yield ETFs, $11.5 billion of that in the 12-month period up to July this year (this is based on the biggest 35 junk bond ETFs on Bloomberg).

In the last five weeks up to 8 August, that trend went into reverse, with outflows of $4.2 billion (contributing to the numbers reported in the last two weeks). Although that’s more than 10 per cent of total high-yield ETF investment, in the broader context things look different.

In the last five weeks up to 8 August, that trend went into reverse, with outflows of $4.2 billion (contributing to the numbers reported in the last two weeks). Although that’s more than 10 per cent of total high-yield ETF investment, in the broader context things look different.

The point is that all the additional demand for high-yield ETFs as evidenced from two and a half years of inflows has been easily absorbed by increased supply. Consider the index behind the most popular junk ETF, the iShares iBoxx corporate bond ETF, best known by its ticker, HYG. The underlying index, the Markit iBoxx high-yield bond index, gathers together all dollar-denominated corporate junk bonds with a face value above $400 million.

Since the start of 2012, the number of iBoxx high-yield index constituents has more than doubled to about 960, and the total face value of the index increased by a similar magnitude from $376 to $808 billion, according to Markit.

During this period the amount of new corporate bond issuance has been nothing short of staggering. Consider this statistic based on SIFMA’s data: by the end of this year (assuming current volumes persist) there will have been a greater face value of high-yield bonds issued in the last three years than over the entire decade leading up to 2008.

With this flood of new issuance, the proportion of high-yield bonds owned by ETFs hasn’t increased. The retail investor can’t even keep up with the volume hitting the market. And yet somehow the yield of the iBoxx index declined from 7.8 per cent to 5 per cent over the same period, indicating that buyers outnumber sellers.

While non-ETF mutual fund inflows account for some of that spread decline, I suspect most of the demand comes from traditional fixed income investors such as insurance companies and pension funds. Just four US insurance companies alone ““ AIG, MetLife, Prudential and New York Life ““ own $44 billion of high-yield bonds. That’s more than all ETFs put together. These kinds of investors don’t have to mark their holdings to market unless they become impaired.

And these four insurers pale in comparison with banks whose portfolios are heavily stuffed with high-yield bonds and loans. Consider Deutsche Bank, which held $72 billion of below-investment grade corporate bonds and $95 billion worth of junk-quality corporate loans in 2013 according to its annual report. That’s more than four times the bank’s core equity tier 1 capital.

It will be interesting to see the impact of recent volatility on Deutsche’s VaR numbers. Fortunately for Deutsche Bank, the loans don’t have to be marked to market. These risky assets, funded by cheap central bank liquidity, pay fat yields that pad the bank’s profits. While the bank holds credit risk capital against the loans calculated according to some internal model, I doubt that model includes the volatility of the high-yield ETF market as an input.

However, the high-yield market turmoil has coincided with reports that banks are offering derivatives-based products to customers that provide them with synthetic exposure to junk bonds and loans using total-return swaps. Sound familiar? If a bank decides that a market is becoming riskier and decides to hedge, usually the first to know is the customer asked to take the other side of the trade.

UK motor finance scandal reawakens ghost of PPI

UK motor finance scandal reawakens ghost of PPI

Smoke, mirrors and net interest margins

Smoke, mirrors and net interest margins

The self-fulfilling prophecy of public sector pensions

The self-fulfilling prophecy of public sector pensions

HSBC’s overvalued Chinese bank

HSBC’s overvalued Chinese bank